31st FITS in Sibiu, Romania

- another huge international crowd-puller in 2024

After the successful anniversary celebration of the FITS International Theatre Festival in Sibiu, Romania, last year, the question for 2024 was: Can this great success be maintained and even surpassed with the 31st edition? The Radu Stanca Theatre's festival team and its director Constantin Chriac answered this question with a quick ‘yes’ and set to work.

The ten-day festival at the end of June this year under the slogan ‘Friendship/Friend-Ship’ once again brought together several thousand artists from 82 countries and offered over 800 events - theatre performances, dance performances, film screenings, panel discussions and street performances. Under the slogan Friendship/Friend-Ship, FITS transformed the centre of Sibiu into one big stage.

The ten-day festival at the end of June this year under the slogan ‘Friendship/Friend-Ship’ once again brought together several thousand artists from 82 countries and offered over 800 events - theatre performances, dance performances, film screenings, panel discussions and street performances. Under the slogan Friendship/Friend-Ship, FITS transformed the centre of Sibiu into one big stage.

While stars such as Isabelle Adjani and John Malkovich left no seats free inside, some were still trying to get a ticket for one or other of the high-calibre performances from late afternoon.

Sibiu seemed even more crowded in 2024 than in previous years. This may have been due to the overflowing outdoor programme, but perhaps also to the good weather, with visitors seeking to round off the day with even more culture in the streets and alleyways, in front of the restaurants and on the city's numerous squares after the numerous indoor performances.

Focusing on a minimum was always enough for the chronicler during his much too short stay, and this year that was to be the contributions of the German section of the ‘Radu Stanca’ theatre.

‘Heart of a Carpenter, The Story of a Transylvanian Saxon’ by Sarah Braun was just the right start.

The play by the playwright, solo performer and creator of site-specific shows, which she has staged for theatre festivals in Israel, Turkey and Sibiu, Romania, was premiered in the Protestant Marienkirche

in FITS, as was A Secret About Joy, about the Jews of 1927 in Sibiu, in the Great Synagogue. The artist and songwriter, a three-time Fulbright scholar and professor of performance at the University of Memphis (USA), also contributed some of the live music.

An evening church atmosphere and the uncomfortable seating put the audience in the right medieval mood of the 14th century, in which a carpenter - less gifted in his craft - knew how to enchant everyone he met through his psychological art as a bringer of cheerfulness and joy.

The emotional story, while not quite reaching the psychological depth of Ernst Penzoldt's ‘Squirrel’, was nevertheless characterised by other qualities.

‘Land Beyond the Forest’ and “Rain Dance Song”, conceived and written by Sarah Brown, composed and arranged for this production by Brita Falch Leutert, lent the piece the character of an almost sacred, timeless mystery play.

The Radu Stanca Theatre provided director Sarah Brown with its elite German-speaking cast, including Daniel Bucher, Johanna Adam, Fabiola Petri and Daniel Plier. They carried the performance and really brought the play to life with their skills.

The introduction to the German-language theatre of Sibiu was to deepen the following evening: ‘Die Meinen’ by Dumitru Acriș based on Maxim Gorki

‘Compared to and with performances in other countries, especially in direct comparison at festivals, some theatres impress with their acting skills, while the Romanians too often shine with their Southeast European enthusiasm.’

It was clear from the very first evening that the performers from German theatre must have gone through a special school, and this was proven true in the following performance.

Without exception, every troupe that the Moldovan Dumitru Acriș staged with his directorial skills underwent a change in the acting abilities of each individual during rehearsals. What was mockingly referred to as ‘joy of playing’ developed into deeply emotional acting skills. And this skill had a very lasting effect, be it in Moldova, several times in Romania and also in Bulgaria.

(Acriș stages his protagonists in the spirit of an Eastern school of theatre; he calls himself an ardent admirer of the Stanislavski method. Politically abused and rejected, this method acting regained importance not only in America. An ‘understanding of the role and having to get involved in the play in order to identify completely with the role and be absorbed in it as if you were the character yourself’ may be liked or disliked in the West. In any case, it broadens the actors' inner horizons and enables them to penetrate the role convincingly and deeply). Author's note

A family is on the verge of breaking apart. The parents cannot understand their children's need for freedom, and the children cannot comprehend the rigidity of the parents who want to give them responsibility. Traditional ideas collide with the development of society and everyone dreams of an increasingly uncertain future.

The German Section's production invited the audience to an immersive experience that questioned the limits of tolerance, interpersonal relationships and the sincerity of feelings in an increasingly unstable social context.

Director Dumitru Acriș cast these intergenerational tensions in a crushing light against the backdrop of a changing world driven by the pleasures of an idealised life.

A suspenseful performance about the loss of dialogue, the burning desire for love and the question of what turns us into monsters on the way to finding our own happiness and freedom was made possible with the addition of other experts from the German section such as the wonderful Emőke Boldizsár, Eva Frățilă, Ștefan Tunsoiu and Gyan Ros Zimmermann.

All good things come in threes, as the saying goes ...

‘Georg Büchner, Woyzeck’

Directed by Hunor Horváth & Edith Buttingsrud Pedersen

‘Every human being is an abyss, it makes you dizzy when you look down.’

This Woyzeck also allowed us to look deep into this abyss. A murder committed out of jealousy. And he described how it came about, how he got there and how he became a monster after being robbed of his humanity.

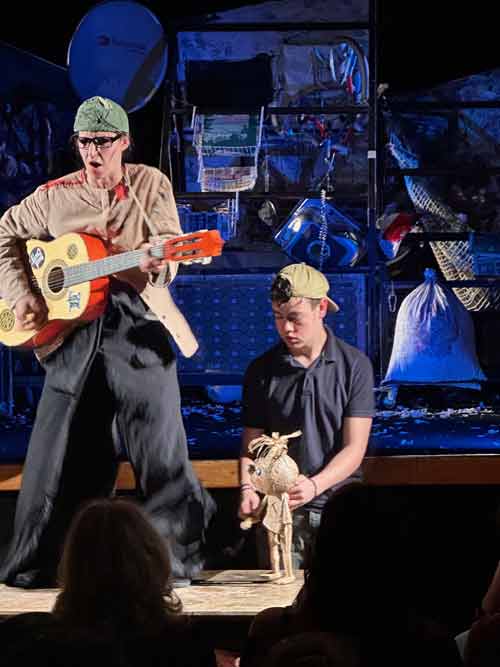

The question of the conditions under which violence is born. Woyzeck, father of an illegitimate child, a humiliated subordinate, the subject of a medical experiment, victim, perpetrator, do-gooder and Marie's murderer. The audience was a guest in a circus performance and once again witnessed the human tragedy of a society heading for self-destruction.

Wooden frames covered in gauze opened up to reveal the circus ring of ‘Circus Woyzeck’. Director Hunor Horváth presented the human beasts up close in a cabinet of absurdities as they humiliate and reject their victim Franz Woyzeck.

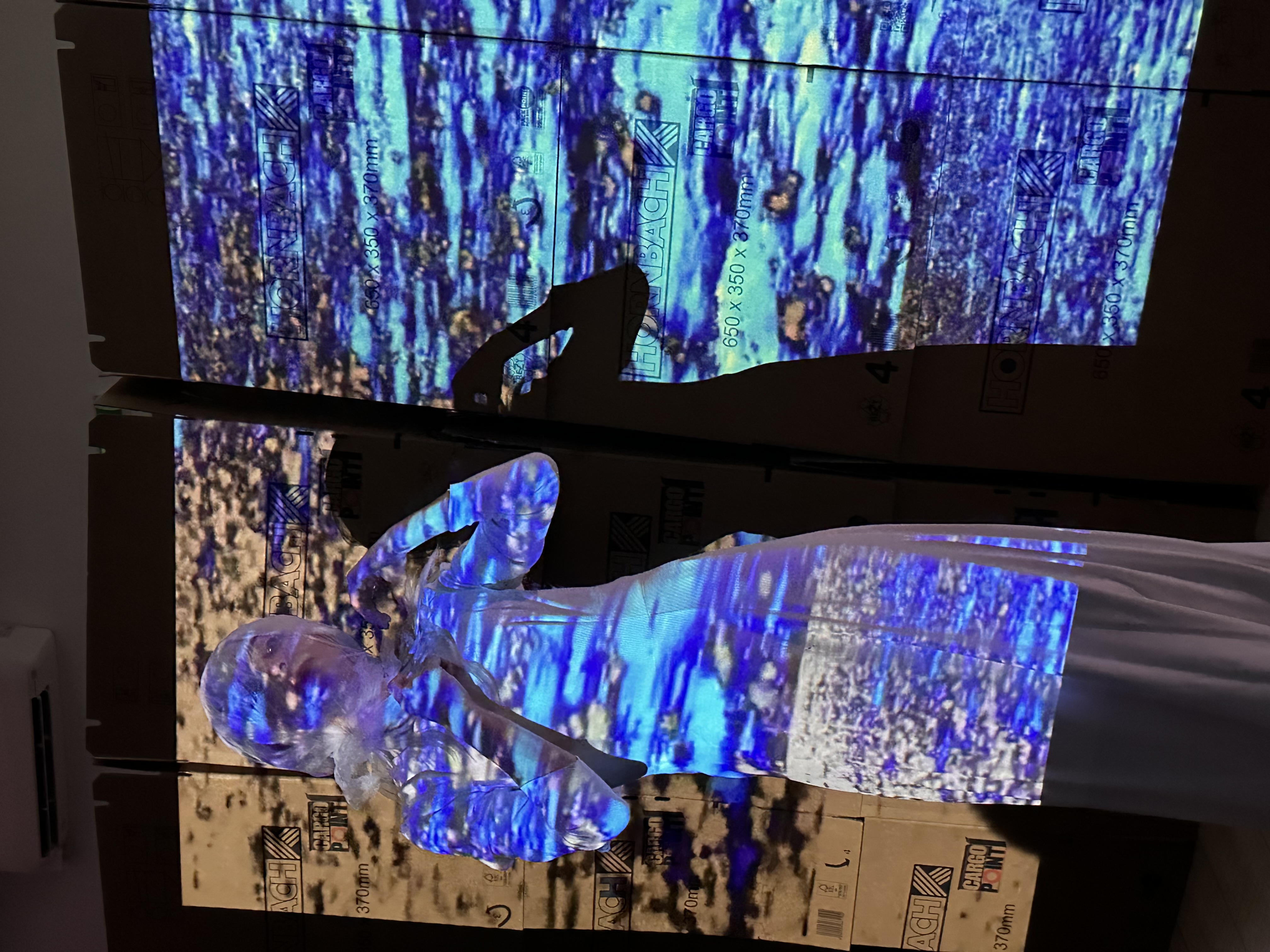

These gates changed again and again and became screens for moving images in order to explore the protagonists even more closely and deeply. Video mapping, lighting and sound design mesmerised the audience and conveyed the psychological moments that Woyzeck experienced, making transparent the deep crisis from which Woyzeck's inner voices emerged and where they drove him.

And all the actors of the German Section once again showed their skills with bravura, less ‘Stanislavski emphasised’, which was good for this production, as it was the interplay of the various design elements that was important here. (The dance scenes were still in need of improvement, as they were often too arbitrary.)

All in all a Horváth production, as one might have expected after last year's staging of ‘The Maids’ by J. Genet.

The visit to the festival left room to report on at least one performance from the Ukraine that belonged - albeit in the opposite sense - in the psychological and contemporary picture: a gripping performance of ‘Caligula’ at FITS (in two different casts by the Ivan Franko National Drama Theatre, Kiev, Ukraine)

Ivan Uryvsky's production of Albert Camus' “Caligula” was brilliant, fast-paced and highly topical. The ‘Stanislavski method’ was exactly right here. Petro Bogomazov created a magnificent minimalist stage set with openings that turned every single scene into a voyeuristic experience.

The play emphasises the need to eradicate dictatorship and tyranny throughout the world, as well as the need to reflect on morality and power. Here Caligula was an all-powerful dictator, deciding the timing of events and enriching himself on the lives and deaths of others, a lesson on the power of madness and the madness of power, a necessary and painful reflection on a present threatened by the spectre of self-destruction.

The madness of contemporary tyrannies came frighteningly close to the audience, filling the room with the stench of its arrogant, brutal pestilence.

Back