after a lecture in the frame of TRIGGER 2021 showcase in Ljubljana by Pia Brezavšček and Rok Bozovičar

a little bit if this and that

Somehow we have become accustomed to the fact that crises have been shaping the discourse on culture and art for more than a decade. But this moment in time is indeed non precedential. Last year was a turbulent one here in Slovenia. Not only due to the coronavirus and the public life lockdowns, which have tremendously paralised the cultural sector, but also because of the many heavy blows cultural policies have struck to the scene.The government’s attitude towards this field expresses ignorance and insignificance. For a year now, Slovenia is again under the right wing SDS government led by Janez Janša, and the minister of culture is from the same ruling political party. The conjunctural government in 2004-2008, when the Ministry of Culture was also headed by dr. Vasko Simoniti, who is a Minister also at this moment, back then tried similar maneuvers as today, but their approaches were more timid and restrained. The current situation is much more brutally direct, professionally unacceptable, and tends to the old forms of conservative censorship in the field of art.

It is exactly culture and the media sector that have been in the first front of this government's maneuvers. With the reforms in the sector, they are executing their politics of resentment. After several liberal governments, the coalition's official interpretation is that culture and media are under the leftist siege and they are freeing it from the occupation by making it more “balanced”, which means they are trying to delete every critical voice. The means for this mission were to date: a.) complete replacement of all the cultural commissions members, b.) political appointment of leaders of public cultural institutions, c.) economic censorship of critical media voices, shutting down financing of the Slovenian press agency etc.

What is more, the neoliberal municipality of the city Ljubljana too profited from the lockdowns and shutting down of public life and in the meantime executed the demolition of the squat Autonomous factory Rog, which was a symbol of freedom and one of the few still existent spaces welcoming to grassroots organisations, artist, activists and refugees in the more and more turistified city.

At Maska journal that we are currently editing, we are about to publish a bilingual issue concerning all these topics in much more detail. For our presentation today we chose some previews and quotes about the topics that depict the current situation we found ourselves in. Despite that we are a performing arts journal, we can hardly focus on the topics in the field itself, as our very existence is under question. As we speak, we are being sued by the Ministry of Culture to leave the spaces at Metelkova 6 in which we and 17 other civil society initiatives and cultural organisations have their offices and most of them are continuously and legally using them for more than a quarter of a century.

Because of all these government maneuvers, mixed up with exceptional times due to Coronavirus, the whole of the event sector was disabled for over a year. The first lockdown decree and with it also the closure of theatre venues was issued in March 2020. There was a gap of summer and early autumn months where limited events with small audiences could take place, then again, there was total lockdown from the end of October up until very recently. Surely, these measures were not exceptional for our country and some of them were necessary for the limitation of the disease, but we in the cultural sector felt an “unbalanced” pressure. Meanwhile, the economic sector mostly operated as usual. The terraces of bars were opened before the first theatres with very strict distances and absurdly few people could attend performances. The measures were up until a few days ago so strict, that many theatres and event venues decided not to open as they didn’t make the ends meet. Still, the productions of performances didn’t and couldn’t just stop, as producers and artists won grants and were obliged to show their performances (in any form). There was thus an inflation of video recorded or streamed internet displays. Many were produced in very poor conditions and on the fringe of legality, as there was a strict prohibition of gatherings and a 9PM curfew. There were even bigger problems with acquiring rehearsing spaces. Obviously, there was no one in the culture policy sector to stand up for the sector’s specific needs. It seems as if a clear internal decree was passed to get the (more or less) critical voices in the field of culture to stay shut for as long as possible.

All this concerns the last year, but things have gone a certain, let’s say neoliberal path at least in the last 12 years or so, from the last economic crisis in 2008. For the upcoming Maska, Rok Vevar describes this changed cultural landscape, where there is no more communal public sphere, where things are shared, produced, experienced, reflected and historised. Spaces are lacking in “public time”. The longest present spaces for performing arts are Glej and PTL (Dance Theatre Ljubljana), but many others were obtained for the purpose of the scene in the past 20 or so years (SMEEL, Španski borci, Kino Šiška, Mini Teater). But still. Let us hear out a longer pasus from Rok Vevar’s article:

"The spaces started turning into public architectural shells, where the communities’ cultural and artistic narratives are outweighed by mere consumption of cultural products. In the area of culture too, public spaces have been affected by cultural commodification, which is not producing the public but audiences. The exchange value has largely replaced the experiential value, which is in culture and art essential for the production of the public. Without a shared experience and its reflection, there is no public.

One of the factors contributing to this phenomenon is that both the national and the local public administrations and decision-makers in the area of culture understand domestic performing arts as products (performances and other events) in the same way as the performances imported to festivals from abroad. As finished products that are seemingly created nowhere and have been finished all along. Since performing arts production is usually invisible to citizens, they are usually unwilling to provide for it, or they leave it in intolerable working conditions. /.../

When we talk about the public sphere we usually never talk about public time, because in the case of public events, time is always read as a form of pure present, which is in performing arts associated also with its proverbial ephemeral nature. Public time? Acknowledging its working, intellectual and creative past, its know-how, skills and procedures (accumulated knowledge) would mean that a certain value is attributed to the working processes and experiences it produces (that this work, too, has its currency) as well as a certain possibility of future development. But, of course, all this costs money, which the politics in the Republic of Slovenia and in the municipalities where art and culture are most vital, are not willing to pay.”

When presenting the particulat “art products”, it is very important to know their specific provenances and by that to consider them not only as products. Another thing that helps a great deal is their constant public reflection. In Slovenia, there is a considerable lack of systematic publicity of public event reviews, as these topics are not the most read and thus profitable for the privatised and private newspaper companies. There are (though underpaid precarised) critics appointed to go see institutional theatre performances, but there is no constancy in publicity for the independent scene. In the last years, there were several initiatives from the scene itself that tried to mend this situation. Bunker established Kriterij, which is focused on performances in the Old Power Station and provided the authors and the public with several written reflections per piece. From 2019, there is also an internet media www.neodvisni.art (established by Via Negativa, co-run by Maska), that we now coedit (before with Alja Lobnik), focused on writings about the independent performing art scene (dance, performance, theatre, intermedia, hybrid). We try to cover every premiere and publish contextual articles.

But right now, times are rough for all focal media that still nurture any kind of critical thought or journalistic ethics. There has just been a major economic censorship made by the Ministry of culture that has not granted money for the programmes of practically all major newspapers, radios or journals in the country. The biggest blow was made to Radio Študent, the oldest independent student radio in Europe, which emits a distinctively unconventional, critical and minority inclusive program. The radio, which was traditionally receptive also to the independent art scene and included its reflection in its program, was this year almost cut off from all its funding. Firstly by its founder, the ever more business and private profit oriented Student organization. And secondly by the Ministry of culture that otherwise granted it a considerable part of its finances consequently in the last years, but this year granted it no funding at all. The media that got financed this year, are explicitly pro government oriented, even established by the near the government officials or catholic media.

In order to clarify the cultural-political context properly, we must also introduce you to the political changes to the tops of leading national institutions in the fields of culture. Last year, the directors of several museums left their positions: despite the opposing opinion of the councils of the institutions, representatives of various professional associations and experts – the Ministry of Culture replaced the long-standing directors of the Museum of Architecture and Design, the Slovene Ethnographic Museum, the Slovenian Book Agency, the Museum of Modern Art, the National Museum of Slovenia and the National Museum of Contemporary History, as all of them, with the exception of the Director of the Slovenian Book Agency, were coming to the end of their term of office.

As Tjaša Pureber writes in the forthcoming Maska Journal:

“Although politically motivated changes to the tops of leading national institutions in the fields of culture and arts were already happening in the past, never before have experts been so systematically swept out through the changing of constitutional instruments, introducing procedural abnormalities, and disrespecting the opinions of the institutions’ councils. The state missed no opportunity in changing upper management through enforcing its rights as a founder and through its discretional freedom in the procedures. […] The Ministry of Culture has shown that although legislation provides normative safeguards which include consultation with experts, in reality, this depends on the more or less enlightened position of the decider. And so, the right-wing government began its march through the cultural institutions.”

It has become clear that expertise can be easily directed and monitored through a certain political agenda. Above mentioned “balancing” is the key argument also in the field of expertise – even to such extent that the Ministry of Culture dissolved all of its expert commissions and formed new “balanced” ones. The results have been above mentioned problematics of media sector, nevertheless the biggest test and key indicator for the future perspectives of independent performing arts scene will be at the end of the year when a 4 year program support (or tender) will be decided by the newly established expert commission, combining both absurdity of the system of bureaucracy in arts and culture, and the depressing uncertainty of future, which depends on governmental affection.

Let’s return for a moment to the political replacements of directors of public institutions. It should be obvious that changes could also occur in the field of theater if timing and opportunity were different. And that is why the silence with which the managements of institutional theaters accompanied all these changes is all the more significant: knowing that they might find themselves in a similar situation, they neglected their role in the public sphere, clinging to their own privileges under a mask of public function.

Speaking of institutional theater, it makes sense to roughly sketch the relations of the theater scene. The most common is the division according to the mode of financial support, which divides the field into different stakeholders. State or municipally estasblished and funded institutional theaters, program-funded NGOs, project-funded NGOs and self-employed individuals.

Firstly, the network of state or municipally funded theaters have maintained the relatively traditional structure. As an institution it has modernized in order to pursue its symbolic and economic value mainly by elaborate communication, public relations and marketing strategy. But at the same time fearing any risk, whether economic or artistic, resulting in aesthetic boredom and predictability of fast paced production that could not stop even during lockdowns. Their financial support depends on state budget breakdowns and potential cuts, but is nevertheless relatively constant, providing salaries for employed ensembles of actors, and fees for external artistic collaborators (directing, music, stage design, playwriting, often dramaturgy) without which the theatre field would not function.

Secondly, the rise and establishment of professional institutions in independent culture throughout the country coincided with the emancipation of different types of youth and student organizations, which had their own financial resources and implemented their own policies, including cultural policies. Apart from alternative culture, they also supported civil society initiatives, minorities, LGBT, ecological and other counter political movements.

Independent theatre producers are a part of the systematically under-supported sector that is heavily dependent on public tendering options. Public discourse is flooded with hate speech towards independent art and intertwines the narrative neoliberal basis of “parasites of public finances” and “unnecessary cost”, as well as pacts with right-wing populism of intolerance – independent production often thematizes neuralgic social themes (continuing its historical development), thus igniting an already heated atmosphere, and consequently becoming the enemy of political “balancers”.

A few words should also be devoted to the personnel arsenal of the independent scene, the self-employed, who fill both institutional and independent spaces. Clearly enough, they are the most creative, productive and vulnerable as well as politically completely unrepresented. That is why Vevar puts it like this:

“The marginalisation and stigmatisation (“public budget parasites”) of self-employed cultural workers is connected to keeping the price of art and culture in Slovenia at its lowest possible level. The politicians are not willing to provide public money for the production of artistic and cultural knowledge and products. Such marginalisation also causes the value of those employed in public art and cultural institutions to go down. This makes art and culture in Slovenia very cheap.”

So, what could we say about the current state of the independent performing arts scene?

If in recent decades independent spaces have been a fertile ground for theatrical experiment and occasionally also an alternative to traditional, established artistic procedures and institutions, and then later as a place for non-established artists who test and seek entry points to larger institutional stages with innovative, unconventional means and striking gestures, today’s independent scene cannot follow its historical impetus. On the one hand, the transition of the younger generations to the institutional framework of creation, if we leave aside the working conditions and long-term blundering with the label young, is extremely quick and easy. On the other hand, independent spaces have also lost the charm of alternative and the possibilities of failure and (re)search, or they are no longer persuasive to such an extent that engagement would not be the result of a gap in career flow.

To put it plainly, it is not enough to portray the independent scene as a mere opposition to the institutions, why they are quite intertwined and transient as artists work in both spheres. Even the ways of establishing its identities are similar: institutions mostly on the basis of national significance and character, assumed symbolic and artistic values and traditions; the independent scene mostly by repeating the identity traits of its historical role, but often by external causes, whether social, aesthetic or economic, in which the influence of European funding guidelines is not negligible. Any developmental vision of the entire theater field is caught between self-sufficient institutional rigid inertia and independent’s competitive split which completely ignores artistic and issues of content and focuses on means of production. Leaving us on the edge of the start of the most difficult period since the last economic crisis, if not the last twenty years, with many organizations at the crossroads of their own program orientations.

In addition to the prevailing political systemic turmoil, culture has also an internal enemy, sexism, so Maska Journal, to be precise, Anja Radaljac, addresses also the recently revealed sexual violence, especially in the field of theater.

In the beginning of this year Slovenia experienced a hint of what could be called the #metoo wave. It started regionally as actresses from the academies of Belgrade, Sarajevo and Zagreb came forward with sexual harassment and assault allegations against professors, and then in the beginning of February, actress Mia Skrbinac spoke out about the verbal and physical abuse she suffered at the Ljubljana Academy of Theatre, Radio, Film and Television (AGRFT) between 2014 and 2016.

The narrative and responses following her public confession were expected and focused on the specifics of “the case”, its singularity, and produced the usual polarisation: on the one hand, wide support to Skrbinac with #nisisama (not alone), but also a predictable pattern of doubts and suspicions, downplaying the severity of the acts, questioning whether it was the right moment to talk, reasons for it, and, of course, defending the abuser, who as long as I know still holds the professorship at the academy.

Although a series of anonymous reports of sexual violence followed, there were no other public revelations and confessions – no one else publicly exposed herself/himself except Mia Skrbinac, who is a precarious worker, without a secure background, heavily dependent on singular projects and not permanently embedded in the institutional framework. No one with a safer, stable background who wouldn’t risk as much as a young actress at the beginning of her career, and thus supporting both her story and opening up the systemic dimensions of the problem as well, did not expose him-herself.

Moreover, in its reaction, the theater community was able only to respond with a formal support, formulated by the hashtag #nisi sama (not alone). Where were and still are concrete gestures of protection, such as employment, project offers …? However, we cannot say that the scene was not shaken or boiling underground: the cancellations of cooperation due to anonymous accusations of sexual violence were hidden from the public’s eyes, while, for example, these days a Jan Fabre’s play is premiered in the National Theater without any problems. With no hesitation placed in a context in which the projects of creators in question are hiddenly canceled on the basis of anonymous reports, and in which the internationally acclaimed revelation of Fabre’s sexual harassment is completely overlooked.

Independent performing arts scene in Slovenia consists of (postdramatic?) theatre, performance of all sorts, contemporary dance and such. Of the stated, it is contemporary dance that is the least integrally supported, as it is not represented by a public institute or institutionalised in any other way. For it is only the state or municipally established organisations which work as public institutions that have a stable income and less precariously employed producers and artists and are not obliged to run for limited funds regularly.

Contemporary dance scene has quite a few stages, where it is shown. As this festival’s focus is not on contemporary dance, I will just quickly go through all the venues:

There is the Dance Theatre Ljubljana in the Prule area, which was founded in 1984 by the choreographer and dancer Ksenija Hribar, who brought her knowledge from London contemporary dance group, an integral part of which she was. As the first professional dance “company”, it was the emergence of many contemporary dance choreographers, still working in the field of dance in Slovenia. Today PTL is one of the two local dance producers that also manages a stage. But the lineage with Ksenija Hribar’s work has been somewhat broken.

The other venue, predominantly intended for contemporary dance, is Španski borci in the Moste area. From 2009, the nongovernmental organisation EnKnap and its choreographer Iztok Kovač, one of the figures that internationalised Slovene contemporary dance, started managing it, which has since then developed into a contemporary dance centre focussing mainly on presenting EnKnap’s and Kovač’s choreographic works, but also hosting international artists and performances from abroad. Španski Borci works similar to the French model of contemporary dance institutions, where the central role is assumed by the choreographer (as artistic director) and his/her artistic vision. The space is also the domicile of the only professional permanent contemporary dance group, En Knap Group.

Most of - to the two producers unaffiliated - contemporary dance productions, and there are many, still happens here, in Elektrarna, the Old Power Station, despite the fact that it is not an exclusively dance oriented venue. It was opened by the Ministry of Culture in a public-private partnership with Institute Bunker in 2004, which has been managing the venue since. It has developed into one of the most inclusive venues, presenting a wide variety of projects and programmes of Ljubljana-based non governmental performing art organisations and independent artists.

The last bigger contemporary dance venue in Ljubljana is Kino Šiška, which was founded in 2009 in the renovated cinema theatre by the Municipality of Ljubljana. It is thus the only public institution related to dance. But its main program hosts concerts of popular music, dance is only displayed in proportionately lesser amounts and mainly as co-productions with the independent scene NGOs, recently mostly Nomad Dance Academy, which curates an international contemporary dance festival, called Co-festival, on the premises.

Other producers with the focus on contemporary dance and without their domicile stages, are Emanat, run by Maja Dealk, which produces pieces and publishes books; Pekinpah, that lately produce mainly pieces by Leja Jurišič; Federacija, focused on somatic and improvisational pieces of Snježana Premuš and Andreja Rauch Podrzavnik; next - in Slovenia living and working Polish choreographer Magdalena Reiter’s Mirabelka; Flota of Matjaž Farič, which has lately produced a lot of contemporary dance and urban fusion by the young Žigan Krajnčan in Gašper Kunšek. There is Maribor based Moja kreacija and Plesna izba Maribor. One of the last newcomers is the Nest Institute, founded by four young female dancers. Exodos also partly focuses on dance, especially its international post production.

There is a biennale of contemporary dance Gibanica that will take place for the 10th time this year. This time in September due to coronavirus (usually it takes place in February or March). Its aim is to bring together the parcialised production and also its presentation to the international public and programmers. Co-festival was mentioned already, it is a festival that hosts mainly foreign contemporary dance pieces and thus brings some freshness into the scene. But there is also some programming of local dance, depending on the needs. It exists from 2012 when it brought together several other projects and initiatives dealing with internationalisation of and education for contemporary dance. Then there is also Spider festival, which takes place every June regularly for the past several years now, with most of its program on the outside location in Tivoli park. PTL programmes the festival Ukrep, which is ment for younger, prospective dance artists. There are some international festivals that try to decentralise the capital-centered dance scene, such as Flota’s Fronta in Murska Sobota or Performa&Platforma in Maribor or (not only dance focused) Rdeči Revirji in Central Sava (Zasavje, Trbovlje, Zagorje Hrastnik) region.

So let me just quickly add a sketch of independent theatre and performance venues and producers, cultural locations or whereabouts that produce art works in different conditions, some with their own presentation spaces and stages, others only office spaces, so an occasional feeling that the independent scene works in separate universes is not purely aesthetic.

Glej Theatre is bearing the great historical burden of experimental theatre - it was established in 1970. In the last few years it has strengthened its support programs focusing on youth and non-professional creators. Glej theatre production is artistically led by the council, encouraging genre innovations and devising methods. Its uniqueness is a 3-year residency program.

Mini Theatre opened at practically the same time as Kino Šiška

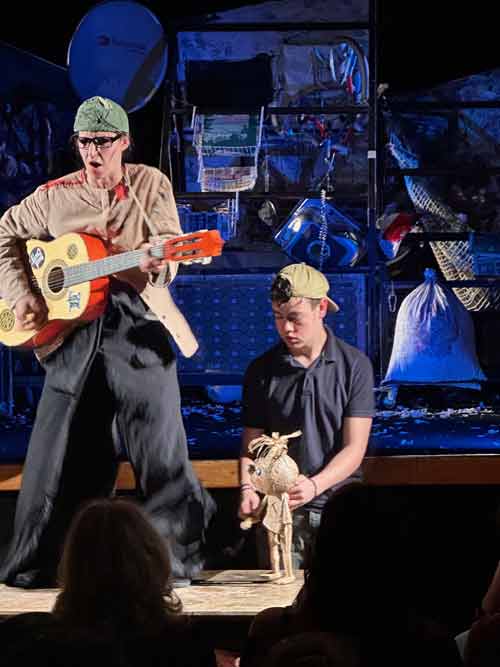

and Španski Borci centres and presents an example of public-private partnership in Ljubljana. The theatre’s director Robert Waltl and his partner Ivica Buljan run the place at Križevniška street. Its theatre production is drama based, usually favoring contemporary drama or popular texts, and occasionally puppet shows for kids.

MOMENT: GT22 in Maribor brings together local nongovernmental organisations and artists, the community-run centre organises a hybrid artistic and cultural programme and is a dynamic venue for a variety of art practices. Intimni stage is dedicated to contemporary performing arts and run by Moment which has established itself as a recognizable force through attempts at reflexive theatrical performances.

New Post office/ Nova pošta is a production unicum – it is a long-term cooperation between the institution (Slovenian Youth Theatre, Mladinsko Theatre) and NGO Maska Institute and is mostly known for its outstanding documentary theater projects, Game and 6 by Žiga Divjak. It is also a discursive space for discussions, presentations and round tables on different theatre and socio-political topics as well as workshops or festivals such as Performance art festival.

There are also many producers without their presentation spaces or stages:

Via Negativa developed a transparent and recognizable approach to the creative process, its aesthetic orientation and strategy are always conceptually designed and convincing in experience. Its artistic director and creator Bojan Jablanovec is also the driving force of the Performance Art Research Ljubljana program.

Delak Institute is dedicated to the development of post-gravitational art and is in its theatre practice employing several formats including informans.

ŠKUC Theatre is the successor of the student movement in the seventies. It was revitalized after the millennium and is mainly collaborating with institutional theaters focusing on Slovenian original drama.

The Old Power Station was already mentioned, it is run by Bunker. Their main production is the renowned festival Mladi levi, Young Lions, combining contemporary world theatre with local emerging artists and is at the same time cultivating a welcoming and sophisticated sense for its social and communal dimensions.

Borštnikovo, Maribor Theatre Festival is the national theatre festival. With every edition of the festival, a question of relations between institutional theatre and independent productions arises, mainly because in recent years independent performances are regularly awarded yet underrepresented, usually mostly in the accompanying program.

TSD (Week of Slovenian Drama) presents the most successful performances based on a Slovene play or text and staged in the last season by Slovene theaters. The main problematic topic regarding independent performances is constantly the status of text in devised theatre approaches.

Back